Türkmen-English Rug Term Glossary

Türkmençe-Iňlisçe Halyça Adalga Söz

By Clay Stewart, San Antonio, Texas, USA © 2007, 2020 | All rights reserved

Introduction

In an effort to respectfully return certain spellings and definitions of Türkmen rug terms to their rightful domain and with the aim of further standardizing their orthography, I decided early on in this project to compile a Türkmen-English Glossary of old rug terms. It is, indeed, a dangerous business. This glossary in not intended as a scholarly treatise by any means but rather as an open forum of discussion to develop and define my many hypotheses as to the meaning of the many symbols to be found in Türkmen rug ornaments. Part of this involves surveying the current literature and historical references, both printed and oral informant testimony. I syncretize what Ifound interesting if not compelling and present my thoughts without my conclusions misrepresented as fact or or as anything carved in stone, but rather as an serious offering. I also felt it important to attempt to return phonetic individuism to Central Asian Türkmen culture. A return, as it were, to their original un-anglicized words. I had a great deal of help along the way from many sources to whom I owe the following debt of thanks: for many translations, corrected mistransliterations and accurate spellings, I am indebted to Prof. Youssef Azemoun, and for others to Sergai Mouraviev. For many modern literary Téké Türkmen language spellings and definitions, I am indebted to Seyitguly Batyrov individually and to the Turkmen-English Dictionary, an SPA project of the Peace Corps Turkmenistan and more recently to the Dictionary of the Turkic Languages and to the Türkmençe-Iňlisçe Sözlük (Turkmen-English Dictionary). Further insights into the orthography, the historic linguistic and ethnographic background, as well as information on the ethnogenesis of major Türkmen tribes comes from Prof. Mirfatyh Zakiev, Moscow, Russian author of ‘The Origin of Türks and Tatars’. I am also sincerely indebted to Joyce Bell Rush of Callison, South Carolina for her invaluable research assistance, her selfless and unyielding support without which this glossary and this project would not have been possible. In addition, I would like to especially thank Donna Endres of Austin, Texas, a member of the New York Hajji Baba Club, and a lecturer and specialist in antique Oriental rugs, for her editorial advice, her tireless contribution of orthographic research and for the gracious loans of her many valuable research materials. And finally last but by no means least I give my deepest and most sincere thanks to the late Mr. N. A. Sahakian, my dearest friend, mentor and teacher who instilled in me the spirit, mystery and romance of the oriental rug which he would often describe as the "ultimate combination of spirit and craft". There is one last special thanks I must give to our webmaster, Mr. Scotty Stevenson, of Walking Fossil Studios in Austin, Texas, for his genius, his patience, his expertise in string code and his exemplary professionalism.

Finally, I am both personally and professionally grateful to Volkmar Grantzhorn's ‘The Christian Oriental Carpet’ for extraordinary information on the absorption of Armenian cultural icons into the Türkmen Steppe peoples of western and southeastern Central Asia by means of copying 'hidden' Armenian Christian symbols into their textile's major gö:ls and minor güls, especially by the 19th century Türkmen Oases groups living in the Merv, Pendeh, Tedjend, and Bukhara Oases during their renaissance of reincorporating 'disappeared’ syncretic forms and techniques of Salyr weaving and infusing them into their own southeast Turkmenian Oasis textiles and their designs. These analyses reveal many fascinating opportunities for further study and interpretation by modern rug scholars of the meanings and origins of many Türkmen rug symbols. As in any investigation, I will attempt to follow the facts wherever they may lead. As I am not fluent in either Russian or Türkmen languages I am at the mercy of translators and the subsequent loss of accuracy. It is true that as I have progressed over the last fourteen years in my research I am forced to conclude that all Türkmen symbols that we know today come from pre-Türkmen Central Asian and Major Asian cultures. It is also apparent that this work is only beginning and that we will hopefully come to understand the process that led to so many Türkmen symbols, ornaments, gö:ls and güls that are so misunderstood. My hypothesis is that Türkmen migration for millennia througout the world created groups like the American Indians after coming across the Bering Land Bridge. Moving south tthey became the Central American Maya and further south to create the Incas and others who exhibit Türkmen culture in their weaving art, their language, poems and dances and religions.

Notes on terms:

The Türkmen language is not currently taught (2006) in any universities in the U.S. or in Canada. Cut off from the rest off the world by their remote and isolated location with Russia prohibiting foreign research on the Türkmen material culture after their military subjugation and annexation of Turkmenistan in 1881. This was a lost and unknown culture to the rest of the world. Tsarist’s intrusions followed by the Bolshevik Revolution imposed the communist statism in Turkmenistan that shut down the region. The absence of a written Türkmen language, coupled with the post-Bolshevik Revolutionary party's early depersonalization efforts through state subjugation was aimed at pacifying the Türkmen groups and their culture that eventually led to Lenin personally hiring Enver to subjugate the Türkmen tribes in order to push their railroad through Anatolia. Russian control of the Türkmen was never completely successful because the power of pagan traditions in Türkmen culture still persist today in Ashgabat. By closing the Türkmen territory to outsiders, many of their old textile terms were adulterated by Russians along with more language replacement by Europeans. They replaced many original Old Türkic rug terms with their own modern loan words, phonetic

mistransliterations and erroneous regional spellings or their phonetic equivalent with imposed Western orthography. This has unfortunately been passed into the west’s current carpet literature, resulting in endless misspellings, mis-pronunciations and mis-transliterations of the terms. The recent (1994) adoption of a modern Türkmen literary language uses the Téké and Ýomut dialects as spoken in Ashgabat in the 1920s over all the other Türkmen dialects. Based on different oral traditions in rug terms throughout the Türkmen tribes, this exclusion sadly sets a path to extinction for many Old Türkic rug terms, securing their future as a dead language. All Türkmen dialects should have been included, then collated and cross-referenced, to remove obvious repetitions and isolate endangered Old Türkic rug terms and then restore them to the modern Türkmen literary language. We owe this to the Steppe Peoples of Central Asian Turkmenistan. Throughout the glossary I shall use the word Turkmen or Türkmen to define the term for both the written and unwritten Turkmen language. Even though the Türkmen did not have a written literary language until 1994, they had a living language before that which I refer to as both the Turkmen language then and the modern literary language now.

Notes on Türkmen pronunciation:

ä is pronounced as in dad

c is pronounced the same as a j in English and as in gentlemen

ç is pronounced as in ch in English so çart is pronounced chart

ň is pronounced as in wing

ö is pronounced as in the German or French eu, as in turn

ş is pronounced as in shirt or shoe, so şot is pronounced shot

ü is pronounced as in the German or French u (tune)

ÿ is pronounced as in yes: when a colon occurs after a vowel, indicating a long vowel and long vowels require the pronouncing of short vowels for the duration of two vowels, long or short vowels determine different meanings for the same word.

ý is pronounced as in yet

y is pronounced as in serial

ž is pronounced as in leisure

Note: At the start of the 20th century, when Türkmen started to be written for the first time ever, it used Arabic script. In 1928 the Latin script was adopted. In 1940, Russian influence prompted a switch to the Cyrillic alphabet, and the Turkmen Cyrillic alphabet was created. The current Türkmen alphabet is a variant of the Latin alphabet as used in the Turkish alphabet with some differences.

Türkmen-English Rug Term Glossary

abrash –

An old Turkish word, referring to naturally occurring horizontal striations in rug fields caused by monochromatic color fading, linearly played out into the weave. Abrash first occurs in the outer exposed processed wool yarns wrapped onto skeins, then in the weaving of that yarn into knots and their fresh clipped tips (or the wefting of flat weaves) when they are first exposed to harsh sunlight. This destructive and explosive mechanical action caused by the sun's bleaching (photon bombardment) and oxidation (loosening, expanding) through heat results in a forced expulsion of dye particulate matter from the microscopic wool vacuoles to which it's attached. This causes a subsequent fading of the exposed convex and conical surface of the wool shaft. As the matter is vaporized the follicle returns to its original state of blonde, colorless, un-dyed, clear glass-like follicles. The amount of wool faded varies with the yarn's position and the intensity of weather conditions. Fading clears dye out of the microscopic vacuoles glass-like mantle on the outer part of the follicle which then acts like a lens to refract light rays and magnify the color underneath upward through the lens creating a lighter look to the dyed wool and a softer, more buoyant, hued patina. Depending on the direction the light rays enter the nap's grain it creates the so called light or dark side of a rug. When light goes into the grain it goes under the wool and they bounces up through the dye in the wool and creates a strong expression of that color. This is the dark side. When the light bounces off the wool going away from the grain it picks up on the clear mantle of the wool and turns the color much lighter, actually bouncing off the wool and not shining through the shaft. This is the lighter side. This effect is buoyed by the presence of lanolin, which should always be in the wool. If not then who knows where the wool came from, dead sheep, sick sheep, damaged wool, etc..

Thus, the magnification caused by a sun bleached follicle's new optical device effect magnifies any underlying dye color to the eye and this effect softens any harshness or garnish brightness, and makes the wool glow. Natural fading is the most desirable method of achieving these softer colors and patina. However natural fading varies with the wool, the dyes and the weave. Modern lime and soda immersion treatments attempting to speed up and duplicate this effect but by stripping (burning) the tips off the knots, thus weakening and damaging the wool. Abrash occurs only with natural vegetable dyes as chemical dyes are usually too stable. Natural fading can be a fairly reliable empirical method of determining the presence of vegetable dyes. Dye remaining below the faded wool is almost always the same color when it is expanded through glass like mantle of the sun bleached wool, unless the dye is compound, then if one color fades, it is one color of the compound and the color that remains (usually a different color) is the second. Various scenarios reflect this process. If a chemical wash is used on aniline dyed wool to artificially create age by bleaching there usually is a third color introduced chemically into the wool and though the effect can be dramatic, it looks burned and is different from the natural process of vegetable dyed yarn fade. Abrash can also be woven in, by weaving in either lighter or darker shades of the same color. After skein fading, the second layer of abrash occurs randomly and evenly across the rows of newly clipped knot tips and to a lesser extent in wefts since they receive less light or use. Abrash occurs less when wool's individual genetic characteristics resist fading due to an inherent ability to fix dye to it and when dye particulate matter is attached with a high degree of fastness by expert fixing or loosely dyed due to the incorrect fixing and by mordants of lesser quality. Exceptions are light and water fast dyes like madder, indigo (which coats the wool with a shell) and natural colored wool. Layered abrash, thirdly occurs when the intensity of oxidation, light, heat and friction, control the rate at which particulate dye matter in vegetable dyes is expelled from the wool.

Color fades from the upper convex surface of the yarn leaving a lighter color appearance when the wool is sun bleached. Abrash is caused first where wool is exposed first, which is the outer curved surfaces of the skein yarns and then after the knotting. Depending on the yarn's position and the fastness of its dye, the fading can be delayed. Outermost layers fade first; inner portions of the yarn(s) located in the center of the skein remain protected and their color stays the same until its exposed. After knotting, fading occurs to a much lesser degree at the protected base of the knot. Fading can be increased if the weaver using assorted batches of high and inferior grades of wool, the latter having faded faster. Friction from use strips color from the wool as well. Rugs stored far away from light fade much slower. Tribal and village weavers are isolated with little access to quality mordants and dyes especially in the country side for Anatolian kelims. Looser dyes are woven into some kelims knowing that it will create faster fading colors, creating another layer of art in faded rural textiles. They don't value expensive dyes from the more populated areas and they don’t consider this a defect. They control the art. The word abrash has (humorously?) been suggested (by H. Jacoby) to be a phonetic mis-transliteration of "hair brush".

ae:lem -

in Türkmen, it means death, elem is the mis-spelling. This relates to the life - death continuum symbology in their rugs, where all things come from dirt and return to dirt. Thus, in my opinion it could be that the so called elem is the fore field of a Türkmen camp, represented by the apron of a Türkmen çüwal, and is the sacred dirt that the tribe dwells on e.g., toprak cult. The çüwal, in my theory, is a symbolic diorama of the actual camp setting, but only in two dimensions. This elem is inferred to be the lower world or underworld. So the lower apron could symbolize the ‘underworld’. The çüwal actually depicts the complete tribal setting, including their yearly migration.

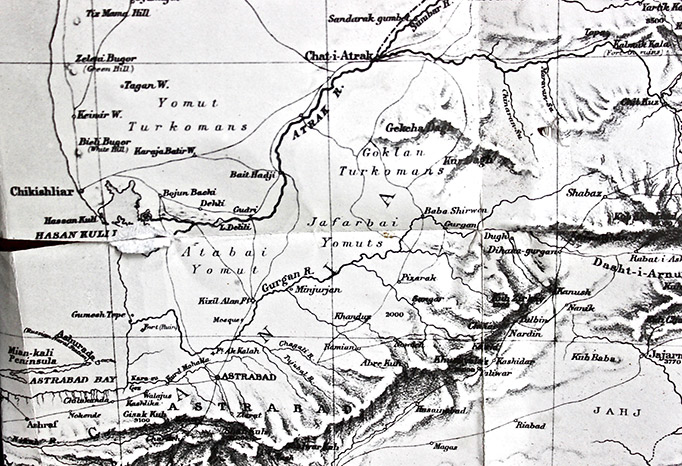

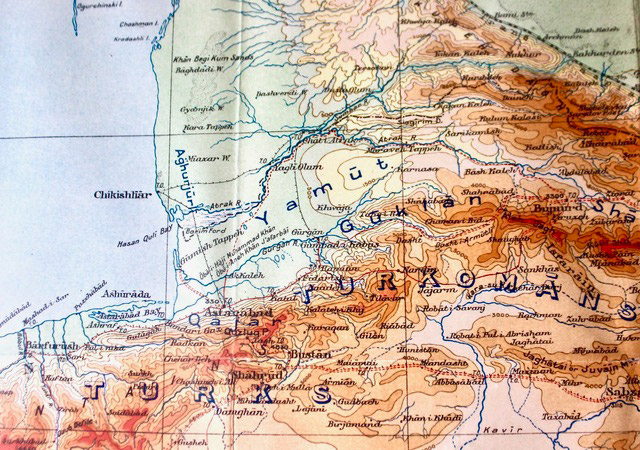

Ahal Oasis - Ahal Téké Türkmen

Aḵāl is the Farsi spelling. Akhal is the Russian phonetic attempt and accepted on most 19th century maps from Europe and Russia. Ahal is the Türkmen spelling. The Ahal Oasis is a narrow, arable strip of piedmont land and spring fed oases extending from the south coast of the Caspian Sea eastwards running between the northern slope of the Kopet Dagh Mountains (aka the Persian Mountains) and the Qara Qum (Black Sands) Desert. It extends for about 110 miles, from Kizyl Arvat in the west to the Murghab basin in the east and ending in the Tedjend Oasis. The Ahal Oasis was previously inhabited by Persian irrigation experts long before the Téké Türkmen arrived. The Ahal Oasis’ name existed as far back as the Parthian Dynasty in the 10th century. Before 1881 and the Russian’s conquest of the Ahal Türkmen at the Ahal Oasis there were no towns in either the Ahal Oasis or in the Merv Oasis. It was populated by migrating and settled tribes of Turkomans, Persians and Uzbegs with agriculture and livestock at least for a thousand years. The towns of Kizyl Arvat and Ashkabad only came into existence after the Russian takeover. Previous Türkmen inhabitants of the Ahal Oasis were the Ali-Eli Türkmen in the 16th century, moving to Merv in the second half of the 16th century, along with an Ärsary group (Ref., Y. Bregel map 36A) followed by the Ýomut, Salyr and Saryk during their migrations.

The etymology of the proper place-name Ahal, a toponym, originates from the Farsi (Persian) and Türkmen languages of the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. Ahal is the correct Türkmen spelling in contrast with the more phonetic Russian misspelling of 'Akhal'. 'Ak' in Türkmen means white. Ahal’s meaning in Türkmen means 1 n 'pure' or 2 n 'white', if 'ak' is contracted to 'a'. And 'hal' in Türkmen means 1 n condition, state, situation, ergo, Ahal could loosely translate to: 'the white place or the pure place or condition or situation'. In the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the definition of Ahal includes a reference to a mystical interpretation of 'hal', i.e., 'hal' refers to a "spiritual state, or an actual experience of a 'divine encounter’". The definition, then, of 'Akhal' or more precisely Ahal is that of a 'pure and or spiritual place’. Perhaps the Ahal Oasis was named Ahal after the pureness of its spring water or the state of mind created by the mesmerizing light of Ahal’s many spring fed oases with their many springs in stark contrast to the nearby sterile desolate Qara Qum Desert. Richard Wright defines 'Akhal' as 'white water', no doubt referring to the oases' springs, but I think that would be 'ak-suw'.

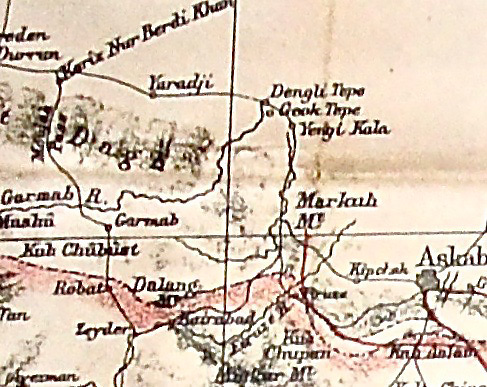

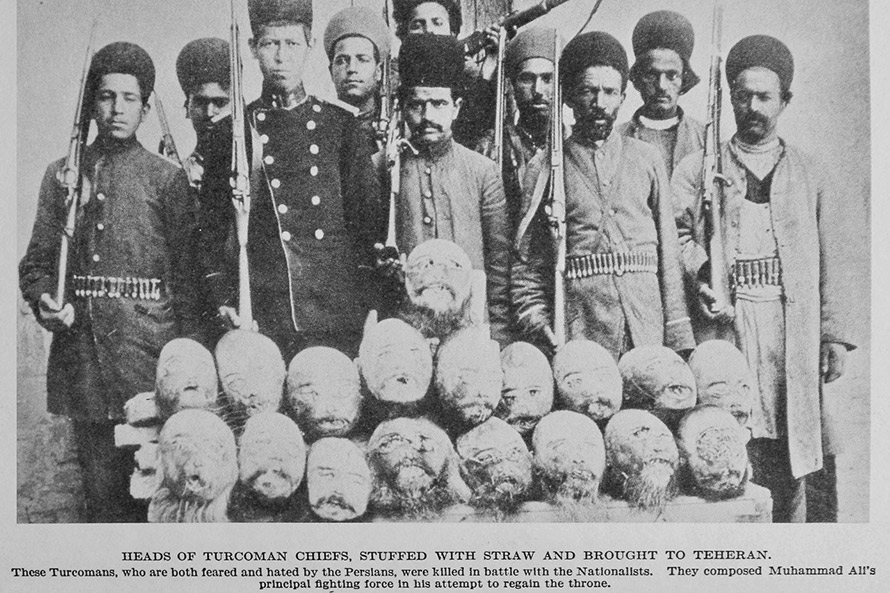

The toponym Ahal in the proper place name Ahal Oasis existed long before the Téké Türkmens’ arrival. The Téké Türkmens adopted their demonym eponymously adding it to their name to become their new appellation of Ahal Téké Türkmen. Y. Bregel’s 16th century map of the area shows the location of the Türkmen tribes in Khorasan at that time and shows the name Akhal Oasis (Russian spelling) long before the Téké Türkmen. I have seen another facsimile of a 16th century Russian map shown on the internet’s Turkotek Salon, which clearly shows an Akhal Oasis before the Téké. In the 16th and 17th centuries the Ahal Oasis was under Uzbeg rule. (Ref., Encyclopedia Islam) In the 18th and early 19th centuries large numbers of Tékés migrated away from the northeast Caspian Sea’s Mangishlak Peninsula south toward the Ahal and Merv Oases (Ref., L. Clark) located in Turkmenia’s southern oases rim. Less than thirty miles west northwest of where Ashgabat is today was the old walled fortress at Denghil Tépé (the ruins of the old fort at Denghil Depe) commonly shown on most 19th century maps as Gök Dépé (simply meaning ’green' hill or mound, not really a place name of the fort but was absorbed as a popular map place marker). The Ahal Téké Türkmen were then led by Tekme, their Sardar (war leader), and a Türkmen. Shortly after his release from the newly constructed Russian fort at Krasnovodsk on the Caspian Sea’s northeast shore he returned to Gök Dépé where he used all that he learned in captivity while covertly observing the construction of the fort and immediately upon returning refortified his old Denghil fortress, doubling it in strength. When the Russian Army’s General Lomakin advanced his artillery towards their newly strengthened massive earthwork and attacked them inside the stronghold, he was severely repelled. General Skobelev soon replaced Gen. Lomakin under the new sobriquet of Commander of the newly declared "Russian Turkoman District'. In 1881, the Russian Army under General Skobelev (who’s military tactic was to shock the enemy into submission by hitting them very, very hard) laid siege to the Ahal Téké’s fortifications at Gök Tépé (the green walled ruins of an old fortress’ tumulus). One month later Skobelev penetrated their defenses using massive explosives and subterfuge. In the ensuing onslaught the routed Ahal Téké Türkmens were then cut down while fleeing trying to escape to Merv, thus finally accomplishing the long fought for Russian conquest of Central Asia that required more than three hundred years of trying to complete.

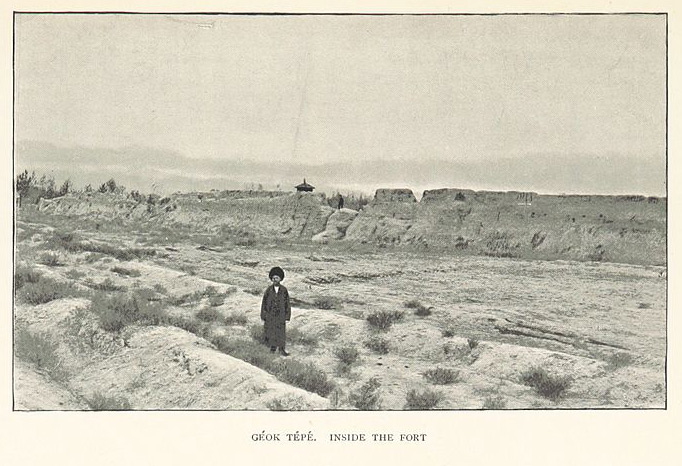

Most 19th century Russian maps of Central Asia’s southern oasis rim in Turkmenia, above Gök Tépé, show Denghil Tépé (Russian spelling) or Yengi Sheher (E. O’Donovan spelling in his map). Hypothetically this is the real name of the ancient fort’s ruins at Ahal Oasis, not Gök Dépé, which really only refers a nondescript 'blue hill or mound'. There is pitifully scant information to be found out about Denghil but it appears to be the name of the ancient tumulus found inside the southeast corner of the old Ahal Oasis fort’s ruins, so-called Gök Tépé, which enclosed a square mile or more with mud walls 18 feet thick and 10 feet high on the inside and a 4-foot dry ditch on the outside. Denghil Tépé was the actual name of the Ahal Oasis’ old fort. Denghil in Türkmen means: 'to try' or 'trying', therefore: 'the place of trying or the trying place'. Indeed, it must have been.

In Türkmen dili (grammar), gök means 1n blue and 2 n green, and tépé means 'wall' as in the walled ruins of a city or fortress' mound. On the other hand in Türkmen dépé means top, mound, hill or 'tumulus', which are ubiquitous in the Ahal Oases strip and are usually found covering over ruins of ancient cities and fortifications. Note: The Türkmen considered it unlucky to live on top of someone else’s ruins. In 1869, at the Geok-Tepe (Russian spelling) site of the old fortress’ ruins a new fort was constructed inside the walled ruins of the original fort (called Denghil Dépé) by the Ahal Téké and inside its quadrangle was the ancient tumulus called Denghil Tépé. In the second half of the 19th century it became the Ahal Oasis’ stronghold of the fierce Ahal Téké Türkmen. I use the second meaning of gök as 'green' as I like 'green hill' for the name of the mound rather than 'blue hill'. Green is the most common usage in Türkmen dili of gök even though it is listed as second after the first meaning of 'Gök' as 'blue’ in the Turkmen English Dictionary.

An example of Gök as green is the Gökleng (Türkmen) who were named for the mythical "green hobbler" (where Gök in Gökleng means 2 n green and 'leng' means 1 n hobbler, lame. This legendary 'green hobbler' who destroyed Mecca when it was originally in Turkmenia but was then moved to Saudi Arabia is why the Ýomut hate the Gökleng.

The name Téké (pronounced takka) is the Türkmen word for a 'male goat or ram', whom they, as animal worshippers, revered and venerated its strength and power. These Türkmen pastoralist stockbreeders worshipped their animals for beneficial traits and blessings that they might bestow upon them if they are well appeased. They believed their ancestor’s spirits lived in their animals who were considered to possess souls and often treated markedly better than their own family members. Goat, spelled geçi in Türkmen has the same meaning as Téké. Thus, the Téké were the 'Goat-man' or more specifically the 'Ram Türkmen'. A further extension of this translation would be the ‘White Bearded Ram Türkmen’, which is my hypothesis of a loose translation of ‘Ahal Téké Türkmen, where Ahal means 'white beard' (sakgal is beard in Türkmen) and the 'A' in Ahal could be contracted from 'Ak' as in Akhal (then A and Ak mean 'white' in both cases). The root of sakgal is ak, i.e., white, while aksakgal (ak sakal) in their jargon refers to 1 n a respected man over fifty or 2 n a village elder, an elete elder, both no doubt referring to a 'white beard of an old man' or in the case of the Ahal Téké Türkmen, the white beard of a old dominant ram. Ram is a specific animal totem and the primary ethnonym of the Téké Türkmen tribe. White (ak) is considered very sacred as is any white quadruped, bird, or natural phenomena, including, perhaps, a vanquished tribe’s spirit or the 'sunny fire' of the celestial sun producing a terrestrial fire’s link with 'celestial fire'. Often mis-spelled Tekke, Takka or Tekky, the Téké were one of seven historical Türkmen Central Asian steppe tribes of animal herders in the 19th century specifically in the southern oases rim of Turkmenia and one of the five major 20th century tribes still existing today. The Ahal oasis is the source of their eponymous name. The Ahal Tékés (and Merv Tékés) were populated primarily by the Beg Téké Türkmen tire. Ahal Tékés were one of the few Türkmen tribes that practiced agriculture. More isolated and off of the major trade routes the Ahal Oasis was much more impervious to outsider and Persian influence than the Mervis. The Ahal Tékés prevented Imperial Russia from seizing Turkestan (Turkmenia) for several centuries and they were the very last Türkmen to be defeated by the Russian Army’s annexing Central Asia.

Ahal Téké -

Gök Dépé or Tépé was the 19th century stronghold of the Ahal Téké Türkmen tribe located in the Ahal Oasis and source of their eponymous name. The Ahal Tékés were populated primarily by the Beg clan of the Téké Türkmen group. The Ahal Tékés were one of the few Türkmen tribes that practiced agriculture. They also single handedly kept Turkmenia out of the hands of the Russian army for centuries.

Also spelled Denghil or Denghill, appears next to Goek Tépé in this map, and in most Russian and Western 19th century maps of the area. Dengli in Türkmen means 'trying' or the 'trying place'. In Türkmen, Tépé means 'a circular wall' or 'walled' as in a walled fort, city or mound where the 'circular wall' is the 'Tépé'. Dépé refers to a raised mound' and Gok (not Goek) means green in Turkmen. Gok Tépé, then, is the Türkmen name for a green mound that’s enclosed by a circular wall and there is such a tumulus in that same area in the east Ahal oasis, which is earthen walled. Dengli was likely the actual name of the old ruined fort, or it’s location, where the 19th century Ahal Teke Türkmen quartered and this is incorrectly referred to as Goek Tépé in the Russians’ 19th century maps, in effect, naming the old fort 'walled green mound'. The actual name of the old fort is Dengli.

Ak Altyn -

white gold, cotton

Ak Öÿ -

White house literally, in Türkmen, a new tent home is said to be an ak öÿ, the dome of which was endowed with supernatural powers. To a Türkmen it represents a smaller sized version or microcosm of what the Türkmen sees all around him. A ornamental composition of seven to:rbas are formed around the flu, their open ends pointing up towards there stars, the öÿ's dome making a circle around the flu. The Türkmen believed that the sky and the Earth are divided into seven layers, each of which is represented by an angel and each angel had a specific influence. These names corresponded to the seven days of the week. The seven borders in a to:rba represent these as well as other forms having ‘seven’ linked to them. The arrangement of them is of importance. It is my opinion that the öÿ's sacred dome hole was used for celestial evocations and incantations. The star's and their positions were accessible through the dome's roof wheel which represents the entrance to the heavenly world or heaven's gate. Star energy was conducted along the star pole (the north pole star is the closest to earth, and the most visible from the north pole) down through the flu into the respective to:rbas, and when collected in each one, thereby harvesting beneficial star energy according their purpose. Blessings for good fortune could occur for good hunting, good crops, abundant fertility, good health, etc.. Their tent was a three-dimensional model of an Ahal Téké Türkmen main gö:l, an octagon, the same form of the tent octagon, and at the roof wheel at the dome's center is a star cross and in the center of it is the sun. These placements were necessary for the Téké Türkmen to navigate the cosmos of potential blessings associated with their star energy harvesting rituals.

ak süw -

Türkmen expression for ‘sweet white water’, ak is white and süw refers to moving water, as in a turbulent spring or flowing river water that breaks into a turgid white water. This seems to be part of the Türkmen water cult and is a totem word i.e., sweet running water.

ak ÿüp -

this is a ceremonial white tent band. White is a sacred color with apotropaic functions and a symbol of status and rank. White ground, embellished ak ÿüps are for such formal occasions as weddings and receptions. White wool is specially selected from all wools and is more valuable and it is also given special significance in other venerated white entities, like camels, cattle, horses or white tents. White signifies the powerful masculine yang life force of sunlight, the provider of life. The male force.

a:la ja, ala ÿüp -

ala (a:la), adj 1 variegated, ala ja (charm), also a plaited rope used to hang the wedding curtain at the rear of the tent and to suspend talismans, composed of two contrasting colored wool strings, usually black and white, plied together, to make one ala ja. The dark/light on/off binary movement effect, in the form of a positive/negative conducting channel, to pulse negative energy and conduct it away from its target. A perfect model of dynamic processes in a straight line.

a:la ja, a:la ja -

n 1 charm, 2 a minor border pattern consisting of diagonally slanted alternating stripes of white and black, repeating in a line and functioning as a conduit for channeling ‘star energy’.

alaman -

Türkmen word for one of their legendary lightening raids.

algam -

1 lightning motif, 2 repeated horizontal linked S pattern found in narrow minor guard borders on smaller rugs.

Altyn dépé -

1 Altyn n gold, 2 dépé n hill, mound, ergo: 'gold hill'. A toponym, Altyn Dépé is the location where a 1981 excavation took place in the ruins of an ancient Indo-Iranian Bronze Age settlement that existed in southern Turkestan from 2500-2000 BC and was abandoned around 1600 BC. Altyn Dépé is located about half way along the old trade route between Ashkabat and Merv, and was closer to the east end of the Ahal Oasis and was undoubtedly a potential source for many of the Ahal Téké and Merv Téké Türkmens’ rug symbols’ designs, which were scattered throughout the ruins of Altyn’s Dépé’s on the painted pottery shards’ remnants, with the same geometric red designs as seen in Türkmen textiles’ designs but predating the Türkmen. The Indo-Iranian inhabitants of Altyn Dépé were known for their proto-Zoarasterian Ziggarat and their bull cult, worshipping gold busts of bulls.

animists -

Altaic peoples who believed that non-human entities contained souls

Anahita -

early Central Asian wide belief in the Goddess of Fertility, the female goddess of fertility, her name Anahita and this belief was adopted later by the Türkmen.

anthropomorphize -

when you talk about a thing or an animal as if it were human.

apron -

see elem, ae:lem, the lower skirt or apron (Sahakian) in a Türkmen çüwal represents the lower foreground field of the encampment (author’s opinion) and also the underworld. See ae:lem.

archetypal gö:l -

Each of the five major 18th and 19th century Türkmen tribes had a single hereditary gö:l which is unique only to that tribe and essentially heraldic, historic and symbolic in function. It is possible that these are ancient gö:ls and they reappear over millenia, possibly rediscovered. It is the emblem that identifies them (much like a high school or college insignia combined with colors in American culture or a family crest in Europe) and is theirs alone unless they lose their independence to another tribe, which then has the historical right to use the vanquished tribe's gö:l in their own weaving and to require the vanquished tribe to use the conquering tribe's gö:l in place of the gö:l indigenous to the first tribe originally. There is ample evidence to suggest a recurring design implementation over time; and the reappearance of certain design elements and ornaments throughout ten centuries indicates there was an overall design pool that possibly outdates this period, suggesting an even earlier archetypal (recurring) ‘gö:l pools’ from which all groups, in one way or another, borrow or readapt their designs. This repository was universal and available to any of the tribal groups, as a common and reoccurring archetypal design heritage, who then reappeared themselves, over and over, throughout the length of the cultures; despite certain self-styled ones that were kept to certain tribes only, apart from the others. The designs and their elements were recorded in rugs, textiles or other other cultural remains like pottery shards, coins and wall paintings and were copied from those into the Türkmen rugs.

The Türkmen venerated birth, death, marriage, their animals and certain virtues as shown by their symbols and rituals. They venerated the eternal continuum of life and death, represented by a ‘never ending birth canal’. They are born on a rug, live on a rug, marry on a rug, and die on a rug. The rug’s symbols encode their relationship with the cosmology, depicting their three metaphysical worlds of spiritual and human existence. Each gö:l also represents a male female dyad unit living in an octagonal tent in harmony with each other in a true unity of opposites, and with all the other dyadic units in the tribe. The apron depicts the actual field in front of the encampment or the fore ground and the Türkmen main border shows the path of the sun orbiting around the tribe, light during the day and absence (dark) at night as it travels around the tribe on its yearly journey. The octagon also represents the sun star in the shape of eight point stars. The language of these ornaments is consistent and universal and their symbols are religious and cultic, syncretically borrowed from Judaism, Islamism, Universal Sufi Brotherhood, Buddhism, Shamanism, Paganism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Devil Worshippers (Yazidi), Manicheanism, Pre-Islamic Semetic occult sciences, religions; and are all both totemistic and talismanic and combined with steppe animism.

Their omnistic textiles are filled with a elegant two and three-dimensional symmetry, both in their ornamentation and their structural design. This reflects their inherent need for order, offered in the form of the rug’s portrayal of all the systematic and balanced representations in their relationship with their magical world and in the non-verbal language of this ethnographic codex. They represent the codex in the material culture of their textiles, ornamental jewelry and tents. What they see outside their tents is the macrocosm of their outer world and they systematically codify that world into a cultic and talismanic working model of the causality of that world in which they can gain ritual control over their environment. A tent then becomes, in effect, a three-dimensional gö:l itself, a magical device capable of balancing powerful ritualistic inter-relationships with their surroundings and creating these structured balances throughout an eternity of trial and error that defined those rituals. These tribes must have this balance to coexist in their chaotic world and this is reflected by the remarkable symmetry of the ornamental structure in their textiles and in their tents. The structure of rugs reflect the Türkmen historical view of the cosmos made up from a nonverbal language of symbols that reflect the essence of their being. Tents and rugs are three-dimensional mandalas that work simultaneously, inwardly and outwardly, socially and spiritually, steering them through the dangers of the world through its causal connection to its beneficial effects. (deus ex machina?)

Ärsary Türkmen - or Ar Sary, Arsary, or Ersarï -

(Jürg Rageth), or the western spelling of Ersari. One of the five still intact Türkmen tribes whose anglicized spelling is Ersari, Ersary, Irsari, in our current western literature. One of three large Türkmen tribes in the 19th century Central Asia steppe and one of seven major 19th century historical Türkmen tribes (or one of eight, depending on your expert, and their criteria for selection). ‘Ar’ or ‘er’ translates to ‘man’ in Türkmen and Turkic, and sary is yellow or blonde, thus literally ar sary or ‘yellow man’ or ‘blonde man’. Translated as the ‘Yellow Man Türkmen’ or ‘Aryan Türkmen’ tribe. Also of interest is ‘Ir’, being ‘Ar’ is the suffix for Iran, which is itself a phonetic mis-transliteration of Aryan, again with the ‘Ar’. Also, the ‘Ar’ in Arzeri, another Turkic speaking group, Azeri is a mis-transliteration of Ärsary.. The Ärsary were quartered on the eastern bank of the Amu Darya river area and during the 19th century were under the protection of the Uzbeks and the Khivan Khan, and by cooperating they were spared certain annihilation by the Russian Army during it’s late 19th century invasion, as opposed to their cousins in Gök Tépé and Khiva. Before that, however, more of their commercial rugs appeared at that time in the Bukharan markets than all of the other Türkmen tribes. They immigrated to Afghanistan in the late 19th and early 20th century to escape from Russian pressure. During the 19th century, while located in the Middle Amu Darya are where they wove the largest number of commercial oversized rugs, and many smaller sized rugs, than all the other Türkmen tribes due to the increasing commercial demands of the Khivan, Samarkand and Bukharan markets. Now termed MAD rugs, it was also during this three century period in the MAD that they cross-pollinated their own designs with the other adjoining tribes (e.g., Salyr, Saryk, Arabatchis and Çowdur) located in the same middle reaches of the Amu Darya River (MAD) with all the other tribe’s weavers, creating a great deal of cross-pollinating of designs (chosen from an available design repository that I call the ‘gül pool’), comprised of designs that existed in fragments from past times or remnant rugs left from previous times, unadulterated before more modern adaptations from exposure to new tribes affecting their designs as well, taken from rugs no longer woven, yet still available and copyable. Subgroups of these Ärsary Türkmen include the Kizil Ayak (red foot), Arabatchi, Beshir, (Beshir is Sart dialect for Bukhara and is also the name of a town near Bukhara), and Charshangu. Many of the rugs woven during this period were very large oversized carpets for the domiciles of the region. Ärsary and Azeri are two branches of the Oguz Seljuk line (Seyitguly Batyrov). Both speak Turkic and it is my guess that the two words are the same, and that Azeri is a phonetic mis-transliteration of Ärsary.

aşhyk, ashyk , ashik or ʿās̲h̲iḳ gül -

A small Türkmen rug emblem not seen on large rugs, that are often repeated and enclosed.

As̲h̲ḳ is the Turkic form of the Arab - Persian ʿIs̲h̲ḳ’ or “love”. The word Ashik derives from the Arabic word Asheq, and means the "one who is in love." Ashik in Persian means "a Turkish bard". It still also means (ʿās̲h̲iḳ) or lover, a term originally applied to popular mystic poets of dervish orders and traveling minstrels. Ashik in Hindi means hope, in Arabic it means love, in Turkish it means love and is spelled aşk and pronounced ashik. An Ashyk torba is a ceremonial Türkmen animal trapping with repeated interconnecting Ashyk medallions that have apotropaic powers (to protect from evil) which are unclear yet repeated for extra power and contained within more power enhancing forms and energy meridian lines in their secondary and primary borders.

An archetypal neolithic emblem of syncretic form adapted into a Türkmen symbol. Phonetically spelled Ashik and lit., in Türkmen, referring to 'sheep knee bone or goat knuckle’ ornaments (Ref., Türkmence-İngilizce Sözlük) that were used as dice in a popular traditional Central Asian Türkmen game called 'astralgali'. This ornamental symbol’s motif is also known as the ‘curled leaf pattern’ and is usually seen as a serrated diamond form with a vine inside, often with three other diamond motifs clustered and surrounded by larger outer half-serrated diamond shaped outline. It’s been postulated that older versions of this design have vines or tendrils that show kinks in them or other variations of line irregularities. The serrated or stepped diamonds are enclosed by larger half-serrated diamond outlines, thus four individual serrated diamonds within an enclosed outer serrated diamond. One Russian ethnographer suggests that perhaps the ashik ornament represents archaic grape leaves or clusters and therefore is an agrarian totem. Most often it’s found in the inverted U-shaped decorative, pile weavings of the Téké Türkmens’ gapylyks or kapunuks and ‘baby’ khallyks (a kapunuk for small animals) and, less often, in their ceremonial to:rba sized animal and tent trappings. Also called the dogajik gö:l. In addition it is called (Ref., E. Tsareva) the 'ovadan-gyra', which, as she says, is commonly known by the European-invented term, the so-called ‘curled-leaf’ pattern. This could point to a pre-Türkmen genesis for the ‘grape cluster’ pattern with the Little Balkhan Mountains as the likely place of the early viticulture, ultimately resulting in this agrarian toponym grape cluster emblem, possibly from the 16th century, or a thousand years before.

aşhyk to:rba -

small slender rectangular bag used as a ceremonial animal trapping with the primary Aşhyk gül based on quadruped knucklebones from the goat used for millennia to play a game called astragali. Aşhyk ornaments are placed inside squares to enhance their power and are repeated, also increasing their power. The primary Aşhyk gül is also referred to as a dogajik gül.

asylmak -

v to be hung, or be on. The current western spelling is asmalyk. In the modern Türkmençe-Iňlisçe Sözlük (Turkmen-English Dictionary) it is spelled Asylmak. Note: An asmalyk, in the Türkmen language, is "a thing to be hung, or suspended”, as a decorative textile and ceremonial apotropaic animal trapping hung on the lead wedding camel’s flank in a Türkmen wedding procession. Asmalyks may be a piled or embroidered flat weave, and are usually five-sided, but occasionally are seven-sided. Ýomut asmalyks are the most commonly found, followed by those of the Téké. Asmalyks were usually made in pairs to decorate both flanks of a bride's wedding camel, and were then hung in her domed, felt-covered öÿ, in the women’s section, in the rear.

Astragali -

term for carved quadruped knuckle bones and were an essential part of many ancient games of Central Asia using these dice like objects. One was played using four astragali with different values on each side indicated by lead studs. Another variant involved five astragali, simultaneously thrown into the air to be caught on the back of the hand. The knuckle bones were carved and then drilled with holes that were filled with lead, perhaps the precursor of dice.

atanak -

Türkmen for cross, this being the archetypal Armenian Christian symbol of a double cruciform even though the cross itself predates Christianity. Armenian for cross is ‘hatchli’ or ‘katchli’.

Aÿna Gö:l -

Aÿna means mirror, glass, in Türkmen, it is often anglicized and spelled Aina, and refers to a small rectangular box shaped enclosure with variants of aÿna güls inside, e.g., aÿna gochak gül, aÿna khamtoz gül, and the classic aÿna gül which is also called the mirror gül, appearing usually in small Türkmen rugs, bags, etc.. An aÿna to:rba is a mirror bag for feminine possessions (including mirrors) or attached to her bridal litter as a defensive trapping, complete with the apotropaic significance of the evil deflecting power of a mirror, for the new bride. See phylactic.

Aÿna Kalta -

or sumka, (Téké dialect), or ‘mirror bag’, when used for mirrors, or as a protective bridal litter trapping; Note: nomad men in the Türkmen tent were not allowed to use mirrors, they had to go outside of the tent if they wished to use a mirror, it was a privilege reserved for women only (oral tradition), mirrors were considered too powerful for men.

ayätlyk -

Ayätlyk, another Türkmen term for funerary rug, ayät = memorial ceremony, lyk = a thing for. Sizes vary according to whether a child, adult or an entire family is buried and then each rug is left on the grave, larger rugs covered several graves. Some Turks wrapped up their dead and hung their bodies from trees, thus the tree of life totem. Trees are a point of disembarkation for birds to carry Türkmen souls to heaven or a more chthonic end. One English lady in 1860’s Central Asia, described seeing a Türkmen cemetery where the graves were all covered in red rugs.

Azerbaýjan -

A:zerbaýja:n n Azerbaijan, Azerbaijani, Azeri. Lit.,: “Land of Fire” (natural gas ground vents that ignite and burn are ubiquitous in Azerbaijan). Azeri is another mis-translation of Ar-Sary and Turkic is the language spoken in Azeri Caucasia, close to the Azerbaijan border, whose people speak Azeri, one of the eight Turkic languages. It is easy to understand where Persian fire cults originated.

Bactria -

pre-sixth century kingdom located in the Transoxianan territory in Central Asia which was located east of the Oxus (Amu Darya) river, west of the Sry Darya River and south to northern Afghanistan. Now nearly extinct the Bactrian Camel is an eponym

Bactrian camel -

double humped camel, indigenous to Central Asia, now nearly extinct.

barmak -

Türkmen for finger, gilin barmak motif called the bride’s or bridal fingers motif.

Bogolybubov, A. A., Gen. -

Tsarist military Governor of the Transcaspian region from 1880-1901 and subjugated the major Türkmen tribes, especially the Téké, collecting examples of all their weaving which he catalogued into the first major work on Türkmen weaving i.e., ‘The Carpets of Central Asia’. Upon returning to Russia he presented these (144 textiles) to Tsar Nicholas which now comprise much of the Russian museum’s collections.

bovrek -

Bow and arrow symbol, Türkmen for ‘bud’, used in Engsis’ borders.

Çemçe gö:l -

according to the Türkmençe-iňlisçe sözlük (Turkmen-English Dictionary) since there is a cedilla attached under the ‘c’ it is not pronounced with a soft ‘c’ as in ‘shem she’ but instead as a hard ‘c’ as in chem chee. The Anglicized phonetic attempt at pronunciation is spelled and pronounced phonetically as chemche and is a Türkmen word for spoon; a Çemçe To:rba is a ‘bag for spoons’, also it also refers to the minor secondary gül in a Téké Türkmen main carpet, and to a common minor emblem in many other small rugs, bags, and trappings, etc.. It is essentially a Greek cross with Gochak motifs at the ends (revering the female goddess cult and the fertility symbol of rams horns with four oblique arms radiating out from the center in the form of an overlaid X without Gochak motifs on the tips showing a quartered cruciform overlaid by an X cross representing the ‘four’ totem twice, the inner form of gö:l's center indicating the four seasons: Earth, Air, Fire and Water cults, and twice combined represents the sun star without the outer octagonal outline (reference ‘The Christian Oriental Carpet’), thus the minor form. This design is ascribed to the Armenian Greek cross when shown as a Gochak cross (cross with ram’s horns on four ends). This emblem appears to have had Caucasian influence.

charky palek gül -

Sogdian star burst medallion, charky translates ‘spinning wheel’ or ‘wheel of fortune’ or ‘cross-wheel of Heavens’, a secondary emblem in Türkmen cüwals and Türkmen ha:lyk borders, that are often placed inside shelpe octagons (lit. jewelry pendants) these güls were represented in a form of eight eight-point stars with a cross-shaped ornament in it’s center, inside a octagonal box. Türkmen believed that circles, rhombs, and crosses placed within squares were sacred and acceptable Koranic magic. These more simple forms were created in Neolithic art and passed on. Star based motifs came later as star worship increased in Central Asia cultures. The early pre-Christian cross was a symbol for Sun-fire. The eight facets of a star cross, placed in a horizontal diamond form, surrounding a single gochanak tippped eight- point star. This shiny depiction of the eight pointed star is placed on top of every Türkmen’s skull cap without exception for gender or age to connect each of those individuals to the cosmos. They truly considered themselves 'star’ people. Charkh is Türkmen for loom or spinning wheel. The literal translation of Charky Palek is ‘wheel for raising water’. Other colloquial translations are ‘lucky star’, ’fate’, 'fortune’ and ‘kismet’. Another name for this emblem is the ‘sagdak’ gül (sagdaq is the phonetic mis-transliteration of Sogdian). The to:rba’s minor border ornaments such as darak, tekbent, naldag, and charky palek are all variations of the cross and sun star variant (Ref. The Christian Oriental Carpet). Repetitions of these ornaments in guard borders next to rows of alternating colors (red, dark red and orange) all connect to ancient Persian fire worshipping rituals in their ancient stone temples of 15 foot arched vaults where they continuously maintained purifying fires and were part of the Zoroasterian fire cult. Fire was worshiped in ancient Central Asia as one of the 'four primary elements', i.e., earth, air, fire and water. The ancient worship of fire was probably one of the first things to be worshipped next to the Sun and Moon by early man.

chyrpy -

anglicized spelling is cherpi or chirpi, n., a Téké woman's cloak, usually with two sleeves sewn back and worn like a cape over their head. Color coded to rank a woman's age and status: yashl (green for eternal fertility) for younger women, sary (yellow for good blessings and continuity in life) for middle age women and ak (white is sacred) for older women. Black ones are also for young women. Many colors are used in Türkmen cloth and clothes, each warding off specific evil spirits as well as the stripes in men's clothes which were channeling devices and deceiving evil energy, conducts it along the stripe and evil goes right off the man, with an immediate purifying effect,. as sins flow off along the stripes and evil is channeled away from the wearer of blue stripes, reversing evil spells. Two color braided wool straps, plaited black and white symbolizing the life and death continuum and called ala ja, were talismanic and and energy channelers often used in the tent. One of the primary colors used to ward off evil is blue which is considered to belong to Satan or Malek Taus, so it works when he comes by, if he sees blue, he'll think that evil (him) is already there and will move on. (Yazidi, ‘devil worshipers’).

Cultural syncretism -

occurs when distinct aspects of different cultures blend together to make something new and unique. Since culture is a wide category, this blending can come in the form of religious practices, architecture, philosophy, recreation, and even food.

Çowdur Türkmen -

Choudor was the third son of Kok Khan, who in turn was the fourth son of Oghuz Khan, making the Çowdur direct descendants of the original Türkmen tribe. The Choudor lived in the northeast shore of the Caspian Sea a millennia ago. Arab historian Abul Ghazi tells us they arrived in Mangyshlaq peninsula as early as the 11th century. The Çowdur Türkmen were one of the seven major Türkmen tribes of the 19th century and was the most northern of the Türkmen tribes. Due to political pressure in the early 19th century they fled from the Manqyshlaq Peninsula and Old Khwarezm to the east and southeast settling along both banks of the middle reaches of the Amu Darya river, coexisting there with the Salyrs, the Saryks and the Ärsary, all under the patronage of the Bukhara Khan. 19th century Çowdur rugs were known as ‘Black Bukharas’ for their darker color palette. This was an unusual color for Türkmen rugs and thought to be borowed from the Uzbegs. The Çowdur were located in Old Khwarezm on the eastern bank of the Caspian Sea, above the Kara Kum desert and south of the Aral Sea in northern Caucasia (they are related to the Trukhmen). The Anglicized spelling is Chodor or Chodur in current carpet literature. Towuk Nusga was the major or primary gö:l in their main carpets (in Türkmen towuk is hen and nusga is pattern).

cult -

refers to a sect or symbolic group practicing ritual belief in the veneration of natural phenomena of powerful life forces encountered and revered for that power and courted for it's favorable influence (both good and bad) e.g., animal, plant, water, earth, fire, and the fertility cults, etc.; e.g., in the past Türkmen threw some of their food into a fire before eating it to protect it and revered the sun as the giver of all life and the female goddess in all women (eli beli ende or woman with hands on hips i.e., the birthing position) as the bearer of all children (the ubiquitous fertility cult or the female goddess totem).

Çüwal

n Farsi, it means ‘bedding bag’. In Türkmen it means ‘flour sack’ or a double saddlebag, pocket or pouch, that hangs on a camel and then hangs in the öÿ, or is a unit for measuring flour, grain, etc. It refers mostly to the largest size of a a Türkmen camel bag, usually made in pairs as two single bags, and as such were woven separately as single large envelope or pouch type bags, averaging about three to four plus feet by five to seven plus feet, larger ones came from the Ärsary. The çüwals usually have a piled face though some were compounded flat weaves, each of which displayed the various indigenous adaptations of loan symbols borrowed from other tribes, at different times, along with the ‘dead’ or lost symbols, borrowed from many pre-Türkmen Central Asian, Asia Minor and Asia Major cultures as well. The çüwal’s back is usually not knotted but rather flat woven, presumably so that it won’t wear knots out against the camel’s rough hide. Literally, in Türkmen, çüwal means a sack to store flour. It’s main use is for transporting items on caravans and then when settled, it’s hung inside the tent to be used for various domestic storage, like bedding. The Anglicized spelling is chuval or chuwal or cuwal. Since the cedilla is attached under the ‘c’ it is pronounced ‘shoe val’ not ‘choo val’. The çüwal’s gül design is often a compressed version of the main carpet’s primary gö:l. Both rugs are dioramas of their outer three dimensional world, but compressed into two dimensions when viewed from above (Stewart). Çüwals all have a major or primary ornament known as the primary 'gül’ and a secondary or minor ornament called an 'emblem’ (my stipulated term). Çüwal’s primary gül’s, over time, can also appear in other çüwals, and vice versa, where each acts as a sort of repository for all the other tribe’s 'dead’ gö:ls (like Salyr ‘dead’ gö:ls) from vanquished or disappeared tribes, who no longer exist or who can no longer support or defend their heretofore primary hereditary gö:l. The restrictions governing the use of another tribe’s ‘dead’ or lost gö:ls are more lenient with çüwals than with main carpets, so over the centuries çüwals became a sort of repository for dead, disappeared, or redesigned gö:ls, thus keeping them alive by chronicling them.

Çüwal Gö:l -

Also known as the classic aÿna gül, or to:rba gül, or Salyr gül, and is a flattened, compressed version of the primary tall Téké gö:l. The çüwal gö:l is really a gül used mostly in many tribes to:rbas and çüwals.

dara -

Türkmen for comb, darak, often depicted in the geometric form of a pyramid with four legs.

daghdan -

is an amulet (Moshkova). Ponomarev (Azadi) translates it as mountainous area. The minor border pattern resembles an hourglass placed on its side and repeated.

Dari -

Persian, Farsi language variant spoken in Afghanistan.

Dépé -

mound, hill, tumulus. Usually lying in the Turkestani deserts where most ruins are buried under the sand and often these form large mounds after vegetation grows. A dépé can have a wall around it as well so it can be a dépé and a tépé and it seems as if both words can apply to one situation. Gok dépé can also be gok tépé and often is shown that way on maps, some with dépé and some with tépé but could also be gok dépé tépé i.e., a green mound that has a ancient wall around it as well.

derýa -

n river, Amy Derýa in Türkmen, Amyderýa trans: Amu River, common error: Amu Darya River which, technically, is Amu River River. Located in Central Asia and emptying into the Aral Sea. Latin name is Oxus river. Amu is named for the medieval Central Asian town of Amul.

dichotomous -

dividing or branching always into two parts, binary, nomadic societies are dichotomous.

doga -

n 1 amulet, talisman. The mullah gave me an amulet to wear in order to protect me from danger 2 prayer 3 charm, spell, doga etmek, to charm, put a spell on someone or some thing, lit. means “prayer” (in the ‘Dictionary of Turkic Languages’) in Türkmen. See dogajik, which is a second name for the primary Ashyk gül.

dogajik -

a thing for prayer, also dogalyk: doga refers to the palm of the hand as in a prayer, often depicted as a pyramid with legs, also a talisman carried in a tiny amulet bag (Ponomarev). The dogajik shape of a pyramid is often used in jewelry. Repeated dogajiks(lyks) occur in minor, narrow, Türkmen guard borders, it also depicts an agrarian totem, called the Aşhyk Gö:l, more correctly it is the Aşhyk primary gül and is woven primarily by the Ýomut on their asmalyks. Another name for the Aşhyk emblem is the so called ‘curled leaf pattern’, a possible grape cluster, inferring viticulture and is an agrarian totem (Tsareva). Note: It seems as if there are two different meanings for dogajiks in the current literature where one is a talismanic or amulet design repeated in minor borders often in the shape of horizontal isosceles triangles, and the other is another term for the Aşhyk primary gül in the Aşhyk to:rba.

dozar -

trade term referring to a rug the size of two zars or about 41 inches each, so 41 times two (do) is 82 inches or about 6 feet 10 inches, thus a dozar, which is two zars in length, is around a four plus by seven foot rug.

dromedary -

Single humped camel used for caravan transport and for their soft fleece, refers to its soft, less crimped, cashmere, or body wool under their belly, arms, axilla and underneath its outer layer of coarser, tougher, curly (crimpier) wool that is often used in weaving for Türkmen textiles, where the nomad men shear the wool and the women weave the rugs. In Kazakhstan, a pretty woman is called a ‘dromedary’.

dumba -

Central Asian fat tail sheep wool used for weaving, soft, lustrous, fluffy knots.

düÿe dyzlyk -

pair of camel knee covers to protect it’s sacred knees when kneeling down from any evil on the ground, a ceremonial decoration, düÿe = camel, dyz = knee and lyk = a thing for, thus 'a thing for the camel knees. Used on the lead camel in a ceremonial wedding procession protecting the bride's (gelin's) camel and the bride herself and therefore apotropaic powers are ascribed to it. They keep the camel’s knees pure when he kneels down and his knees touch the ground they are covered to defend them against evil. There were also camels ankle bracelets woven from the camel’s eyelashes.

düÿe khallyk -

a camel collar used in the wedding caravan’s lead camel, they are U-shaped and come in two sizes, large and small, smaller ones were for smaller animals, child sized ones. Talismanic ornaments attached to the fringe were used to protect the new bride from all evil. See khallyk.

duz -

du:z n salt, carried in a small bag, du:z kalta (salt bag) du:z sumka, du:z kap, also salt bags.

dyrnak -

n. Turk, claw, talon.

Dyrnak gö:l -

one of two heraldic primary gö:ls used in Ýomut main carpets. Represented by a hooked, horizontally flattened diamond lozenge, on the outside and various elements found inside its center. From dyrnak (Turk. claw, R. Pinner). Thought by some to emanate through the influence of Caucasian loan symbols.

elem -

phonetically mis-spelled Arabic word widely used in both Türkic and Persian languages and means sorrow, or death. Widely used in current carpet literature to denote the lower apron or skirt of the Türkmen cüwal, engsi or main rug. See ae:lem.

endonym -

is the name for a place, site or location in the language of the people who live there. In contrast, a locally used toponym—i e, as opposed to a name given to them by others—is called an endonym (or autonym) or a name used by a group of people to refer to themselves or their region (as For example, Köln is a German endonym while Cologne is the English exonym for Köln. (ref., Thought Co, internet)

Ensi -

engsi- (‘en’ is Turkic for width, Pinner), is a door sized rug covering the öÿ’s entrance, often quartered with a niche at the top and an ae:lem at the bottom and fastening loops, and is the primary door enclosure for the öÿ’s entrance. Often called katchli or hatchli (which is the old Armenian word for cross), this quartered and compartmented field design refers to the ancient four-principle cult and the three horizontal partitioned sections refer to the three shamanistic life levels of the Upper World Universe (the upper or cosmic level), the Middle Kingdom (earth and man), and the lower cathonic level (zarmin), i.e., hell, underworld. The ensi’s face was usually turned inward, facing inside the öÿ. There are only a few photographs from the 19th century showing an engsi actually being used in the field.

endo-ethnonyms -

what name certain peoples call themselves.

eponym -

An ethnonym is a name applied to a given ethnic group, either by another group, or by themselves. It may be a tribal name, a name given to a specific ethnic group, a geographical name, or a place name derived from a topographical feature. (ethnonym, ethnic).

eponymous -

adjective. The definition of eponymous is something or someone that gives its name to something else.

Ersari -

phonetic mistransliteration of the major Türkmen tribe’s name. See Ar Sare, (also Arsary, Azeri), should be Ärsary.

ethnonym -

An ethnonym is a name applied to a given ethnic group, either by another group, or by themselves.

ethnogenisis -

"the formation and development of an ethnic group." This can originate through a process of self-identification as well as come about as the result of outside identification.

exo-ethnonyms -

what name those certain peoples (tribal societies) are called by their neighbors.

eyerlyk -

in Türkmen ‘eyer’ means saddle and lyk means a thing for, so a ‘thing for the saddle’ i.e., saddle cover for the horse, also for the camel, but not the saddle itself.

Gabsa gö:l -

often referred to as a Kepse gö:l. Second of two primary Ýomut gö:ls depicted in their Main Carpet (ha:lyk).

gapyrga -

rib - tree like or ribbed, opposing serrated branches, usually attached to a gyak pole and found in the lower elem (apron or skirt) of a çüwal or a hatchli. This motif reflects archetypal Türkmen nomadic weaving traditions (Tsareva). It could easily depict flowers or trees in the fore field of the encampment and is connected to both the ‘tree of life’ motif and as an agrarian totem.

gapylyk -

Türkmen word for ceremonial trapping, commonly spelled kapunuk. Literally gapy = door, lyk = a thing, therefore: a thing for the door (in Türkmen). A knotted, upside down, U-shaped textile, with tassels and fastening ropes; a decorative piece unique to the Türkmen and hung inside the tent's doorway. They are also used in the wedding procession to decorate the ‘kejebe' or bridal litter and then placed in the new bride’s father in law’s tent.

geçi –

Türkmen word for a male ram, and a mis-transliteration of Téké, which is the same word as geçi, just spelled differently, but means the same which explains the ubiquitous rams horns in Türkmen designs.

gelin barmak –

gelin n. bride and barmak n. finger, v. to go, to head in a direction, also warning evil to ‘get out, go away’, and ‘mind your own business’. Gelin barmak or ’bridal fingers’ is depicted in Türkmen minor guard border symbols as repeated pentagonal apexed pyramids with three straight sides in outer guard borders surrounding the çüwal that form a sort of electric fence producing a line of energy or protective force surrounding whoever is sitting in the center of the rug,

gochanak –

often misspelled as Kochanak or Kochak it refers to a diamond with double ram's horn motif and is a protective device for the female goddess, new brides and the fertility cult. Ultimately it is a ancient Hindu fertility cult symbol (birth symbol) and is often shown in a repeating sequence of the motif in borders of wedding dowry textiles. This repeated design is a sort of mantra, and gains power when it is repeated, thus becoming an incantation which creates far more potency than just the spell. Double gochanak designs found repeated in the minor borders and Aÿna gochanak are the same, but in a Aÿna gochanak, the gül is put in a rectangular small box that is repeated, usually in the field borders of a bag or a to:rba.

Gök Tépé –

misnomer, adjacent to Denghil Tépé (the actual name for the Ahal oasis which means 'the trying place', lit.. In this case, Gök means 'green' and Tépé means walled, so a 'walled green mound’, where Tépé refers to a 'wall' around a city’, a fortress or simply a green mound. The so called old fortress at Gök Tépé is a circular walled mound turned into a fortification. It's spelled Geok Tepe (Russian spelling) in current western literature. This is the mid-19th century Central Asian home and stronghold of the Ahal Téké Türkmen. The 'First Battle of Gök Tépé' took place in 1879 when the Russian General A. Lomakin’s artillery attack failed and he was forcibly repelled by the Ahal Téké. The 'Second Battle of Gök Tépé' occurred in 1881 when Lomakin’s replacement Gen. Skobolev, ruthlessly deployed his sanguinary conquest of the Türkmen. There are two Gök Tépés on some maps, one northwest of Ashkabat in the Ahal Oasis and one to the south. The incorrect name Goek Tepe has been grandfathered into western literature even though its real name should be Denghill Tépé which was the original fort’s name and the Ahal Oasis was called this. "Skrine says that fort enclosed a square mile or more, with mud walls 18 feet thick and 10 feet high on the inside and a 4-foot dry ditch on the outside, although other dimensions are given. The area was part of the Akhal Oasis where streams coming down from the Kopet Dagh support irrigation agriculture." (Ref., Wikipedia)

Gökleň –

Gö:kleng, Goklan, A Turcoman tribe of Iran that are not actually Türkmen. In the 18th century, they were displaced and then assimilated into the Western Ýomut Türkmen, as a sub-tribe they were specifically located adjacent to the Western Ýomut Türkmen, in northwest Persian Turkestan, by the Gorgan river, in the second half of the 19th century and they were known for their sericulture and sheep herding. There are whole tribes, as, for example, the Kelte race among the Gorgen Ýomuts, which are generally half blonde. The Ýomut of Iran have six branches. They live in central and eastern Türkmen Sahra. Much of the Gökleň weaving is misidentified as Ýomut who are their neighbors to the west and their sworn enemies. Eventually they were forcibly subjugated post Russian incursions into the area in the late 19th century. "The Turkomans recounted, with respect to the ruins (Atrek River area in Persian Khorasan where the Gökleň lived), that God, from a special love to the brave Turkomans, had placed the Kaaba first here instead of transporting it to Arabia, but that a green devil, who was at the same time lame, named Gökleng (green hobbler) from whom the Göklens were descended, had destroyed it. The insolent act of their ancestor is the reason, added the savage etymologist, why we live in hostility with that tribe." Armenius Vambery

gol –

Türkmen n ball, arm, hand, signature

göl, gö:l –

Most Türkmen gö:ls are quartered roundels. Gö:ls are primary Türkmen historical tribal tamghas. When referring to rugs only and spelled with a ‘g’, gö:l means 'lake’ in the Türkmen lexicon, when not referring to rugs, the word lake is spelled with a ‘k’ as in kö:l; a water cult and totem, connected to the sacred earth (toprak) topynym, an agrarian totem (Tsareva’s term) and the eternal life/death continuum philosophy (toprak in both Türkmen and Farsi means tomb) and this idea is associated with all the rug’s symbols, see guş gö:l. It is my opinion that the Türkmen’s original primary gö:l was carried west to Central Asia by ancient Türkmen tribes contrary to discovering it in Turkmenia when they arrived even though Sogdian silk textiles have roundels in them It is also my opinion that the original motif came from ancient China but was modified later by the incorporating animist totems from the Altaic Türkmen and those totems were then venerated a millennia ago in Central Asia's Rum civilization after they arrived in the area in the 11th century.

gö:l –

in modern Türkmen n carpet pattern

goÿun –

sheep in Türkmen.

göz –

n. eye, of the evil eye.

göz-dil –

n the evil eye, ‘göz-dilden saklamak’: to protect someone against or from the evil eye. ‘Dil’ means evil in Türkmen. A magical talisman such as this is called an ‘eye cracker’ because it can ‘crack’ an evil eye by deflecting its evil power back into the evil eye itself, thus breaking it.

gul –

Türkmen n arm, signature. Persian n lake, Farsi, n slave, servant (ref., internet Türkmen English Webonary). Pronounced 'gull' as in seagull. Turkish n flower. Also in Persian it refers to a minor emblem pattern in small rugs.

gül –

Türkmen n flower, Dari and Tajik the pronounced 'gool', this word in Farsi is gol; also the Persian word gul is pronounced in Türkmen as gül which means flower and when referring to rugs cannot be changed to gö:l (lake), nor can it be replaced by the non-rug word in Türkmen for lake which is kö:l. Different spellings of the same word or even different words depend on the use, especially in the Türkmen language.

gülli gül, gulli gul

a large round archetypal Türkmen gö:l, like all others consists of a quartered octagon, where each quarter contains three cloverleaf motifs (replacing the three arrows of the Téké primary gö:l) and resembling the 'clubs’ suite in playing cards. This is the traditional emblem of the Ärsary Türkmen, borrowed from the Salyr and the Saryk. 'Gülli gül' appears to be a misnomer for this variant of a Türkmen primary gö:l or at least an orthographic issue. The Türkmen gül is a minor or secondary emblem to the major or primary Türkmen gö:l. Gülli gül - Türkmen "flowery flower", which the Türkmen would consider redundant and therefore improper.

gurbaga gü:l –

predominate minor or secondary gül used in Téké Main Carpets, gurbaga is the Türkmen word for frog. It is actually a basic Greek cruciform in appearance with a star cross overlay and in no way resembles the amphibian. Animal totem. Animal names reflect the steppe animism of the Türkmen.

guş –

Türkmen n bird, an animal totem, often mis-transliterated as gush, gushly, or gushli.

gushly gul –

this is a misnomer for guş gö:l or 'bird lake' ornament or 'lake with birds', guş or bird in Türkmeni dili is an important animal toponym and gö:l or lake in Türkmen is an important agrarian toponym.

guş gül -

in Türkmeni dili the name bird flower is incorrect and instead a Téké Türkmen main carpet ornament is called the guş gö:l or 'bird lake' ornament. There are no minor emblems in Türkmen weaving called 'bird' and in Türkmen ornamentation 'gül' always refers to a minor or secondary emblem.

guş gö:l –

Türkmen guş n bird, gö:l n lake, both toponyms. This is the historical primary gö:l of the Téké Türkmen tribe and the eponymous name 'bird lake' for an ancient emblem used in Téké Türkmen ha:lyks as their traditional heraldic and identifying tamgha. The actual term guş gö:l or 'bird lake', guş being bird and gö:l being lake, reflect the Türkmen penchant for simple names. Remember they had no written language. These are a bird totem and a water agrarian totem (water is a cult in Asia). In the many layers of Türkmen symbology, the bird signifies both supernatural and vital predatory skills that they adopt to create the protection that comes to each Türkmen who emulate their venerated animal and bird spirits and their pagan pantheism. These fierce and empowering symbols are simultaneously syncretized. There appears such misspelled variants as gushli or gushly in current literature, meaning 'birdly'? To the Türkmen, a 'gushli gul' would mean 'a birdly flower’ which is nonsensical. The guş gö:l is a quartered eight-lobed octagon with various centers and in each quarter there are three three-lobed 'clover leaf' motifs (resembling the playing cards suit of clubs) instead of the primary or major Téké main gö:l with three arrows in each quarter. This design is frequently seen in the late 19th and early 20th century Ärsary Türkmen rugs of northern Afghanistan in the town of Charshanga and which is also an Ärsary sub-tribe.

güza –

Türkmen word for cotton (Western Turkistan), also gowaça and pagta.

gyak –

Turkic word for ‘diagonal path’ (Ponomarev), also means a charm, and resembles a diagonally striped barber pole. Metaphysically, I suggest this is a conductive bi-nary energy channeler caused by dark/light quantum energy activators, the kinetic stored energy in it’s on-off patterns, positive then negative, black/white (energy flows from areas of higher concentration into areas of lower concentration of energy, i.e., nature abhors a vacuum) so a slanted black line next to a slanted white line creates that kinetic movement, from white flowing as good into black as the absence of light energy or negative energy, repeating this progression, as perpetual motion conducts star energy towards it’s polar opposite, the resulting positive energy is channeled toward the bride and the evil is caught by distraction then led away from the bride, amplified by the changing colors of the sun and of fire as additional activators.

gyz –

Téké dialect term for both bride and girl, see gelin, kejebe.

halyça –

Halyça – pronounced ‘haly sha’ in the Téké dialect, it is another spelling for the main carpet, and the Türkmen spelling of ‘rug’, also spelled hali, in current carpet literature, also ha:lyk is the word for Main Carpet. See ha:lyk.

ha:lyk –

correct Türkmen spelling of hali or haly and refers to one of their Main Carpets.

hatchli, katchli –