Clay Stewart Collection of 19th Century Türkmen Textiles

Internet Exhibit Notes

The Galerie Türkmen website’s ‘Collections’ section gives rug enthusiasts an opportunity to explore nineteenth century Central Asian Türkmen steppe textiles in general and specifically the absence of any cogent explanation for their enigmatic symbols. Early Türkmen material culture enabled the merging of Altay steppe totems with pre-Türkmen Central Asian culture’s symbols. As these cultures disappeared, the White Huns, Sogdians and Sassanians, etc., their abandoned artifacts were later re-discovered by westward moving Türkmen mauraders, in their wall paintings, broken pottery shard remnants and ancient Sogdian coins, etc.. Türkmen weavers copied the symbols and incorporated them with their other ancient symbols taken from China, Mongolia, India and Tibet. They crossed the symbols with their own creating the iconic Türkmen emblem we now call 'gö:l'. Twenty-five technical descriptions include curated structural and ornamental analyses and each rug’s provenance. A 50,000 word Türkmen-English glossary defines the old Turkic rug terms and the rug symbol names found in the technical descriptions. Old Turkic rug terms are problematic to substantiate but necessary to standardize the lexicography. Our goal is to return the original Turkic names of Türkmen rug symbols back to their mother tongue. This is not a commercial website but rather an open Türkmen textile forum. The rugs shown here are from my personal collection and are not for sale. This exhibit is solely an effort to increase awareness of these extraordinary, multi-dimensional Türkmen steppe textiles.

By Clay Stewart San Antonio, Texas, USA © 2020 (All Rights Reserved)

The Red Rugs of the Türkmen Steppe

An old Armenian Master once threw a book to the floor and loudly cried out to his apprentice: “Do you want to learn books or do you want to learn rugs? This is the book! This Is The Book!”, he frantically exclaimed, pointing to a rug.

Masters of the Desert

"We Don't Need Kings. We're All Kings!"

Since the dawn of time, in the dimmest recesses of Central Asian history, there roamed fierce Türkmen nomads in an area so secluded and remote that only today are we learning about them. ‘Masters of the Desert’ for untold millennia, they pastured and quartered in areas so incredibly isolated that they effectuated a remarkable material culture, so unique, it would make science fiction movies like Star Trek seem mundane by comparison. Geographically cut off from the rest of the world they became brilliant at animal husbandry, breeding camels, sheep, horses, cattle and goats to enable their herd pastoralism. They transformed their scant local resources into the carefully wrought, stunningly beautiful textiles that lived up to the impossible tests forged by their dessert steppe. Using skills perfected over a thousand years of uninterrupted trial and error they wove plain wool into the ruggedly handsome, moveable textile architecture so essential for their survival in their hostile yet enchanting world. They acquired madder, indigo, silk and cotton through a complex system of bartering and networking, both local and far reaching. They practiced an ancient pre-Islamic Shamanic Altaic pagan animism and they were completely indifferent to the strict formalities of orthodox Islam.

Türkmen nomads were legendary raiders, thieves, brigands and stealers of wives. They were expert dealers in countless Persian and Russian slaves that they captured and later sold in the Khivan and Bukharan markets. When the Russian General Kaufmann liberated Khiva at the end of the nineteenth century he also liberated seventeen thousand Persian slaves. An old Türkmen saying warns that: “No Persian shall ever enter into Türkmen territory unless it’s at the end of a rope”. They would force Persian women slaves to chew cured leather to make it softer for their boots. If the slaves did not sell, they would cut off their hands or feet or both and leave them. They were the most powerful and deadliest mounted cavalry in Central Asia from the late 17th century through the end of the 19th century. They were the only force that stopped Russia’s incursions into Central Asia’s Auralo-Caspian region and southeast Turkmenistan’s Oases areas for over one hundred and fifty years, until 1881. Not surprisingly, they could slit a man’s throat with as much precision as they wove their finest rugs with. informant oral accounts suggest that they would add their own blood to their red dyes as red blood was considered to be the essence of life. Tribal counts taken in the 1840’s Auralo-Caspian region by a Russian army Major Murav’yov, reported in his ‘Journey to Khiva’, that one Téké Türkmen tribe in the Trans-Caucasus had some 50,000 kibitks. At five or more people per tent this comes to 250,000 or more nomads in one tribe, literally a moving city. It has been suggested that the main reason for Russia’s keen interest in Central Asia during the second half of the 19th century was that their normal source for cotton was the United States but that was interrupted by the Civil War so the Russians turned their eyes toward the cotton crops of Central Asia.

A short history of the evolution of Türkmen symbols

Most Türkmen textiles are red. These Türkmen 'masters of red’ produced infinite shades of madder dyed red wool, all dyed by the men. But it was the Türkmen women and they alone who had total control over which symbols they wove into their rugs. Among the more ubiquitous were the ‘Female Goddess’ fertility cult motifs known in Turkish as ‘elle bele ende’ or ‘woman with hands on hips’, referring to their ancient birthing position. Nomadic women were considered more important than men because they could have babies. The Türkmen venerated the women’s ‘never ending birth canal’, as represented by a serrated vertical diamond form often with ram’s horns at both ends. In the center of the diamond symbol (a vagina) is the next little goddess on the way represented by a smaller serrated diamond form in it's center and so on. Also common were the eponymous Ram’s horns (some suggest the Ram’s horns were an ancient Hindu fertility symbol). It’s not surprising that the eponymous name Téké refers to a ‘Ram’ or ‘male goat’. The ‘ram’ is the Téké’ Türkmen’s primary animal toponym whose independent spirit, strength and virility were greatly revered. The Türkmen had no written language so their çüwal’s symbols became a sort of sacred book containing non-verbal instructions. These çüwal blazons became a repository for local ruin’s many archaic symbols found in their abandoned artifacts and for the other Türkmen tribe’s ‘living’ and ‘dead’ emblems as well. These ancient symbols emblazoning their çüwals were taken from Central Asian and Asian pre-Türkmen, pre-Christian and pre-Islamic cultures that the Türkmen discovered when first arriving in these areas and then fused with their own symbols over time. Wherever these artifact’s symbols were found the Türkmen may or may not have understood the meanings of but they assimilated them non the less. They combined them with their own symbols in order to make them their own.

In the beginning their Shaman priests most likely had knowledge of the meaning of these lost pre-Türkmen symbols, but that knowledge died with the last priest and lay dormant for eternity. In my opinion it must have taken eons for the complete transformation of these adopted symbols into Türkmen gö:ls and güls. Previous Central Asian cultures did not use the same non-verbal language of archetypal symbols in their emblems, however, throughout time and in combination with previous culture’s ‘dead’ symbol’s, they eventually morphed them together with their Türkmen symbols. Alternatively, it’s been suggested that certain tenth century Sufi monks came west from the Altai into the Türkmen steppe bringing ancient symbols with them which they gave to the Türkmen (possibly the early Salyr). There were pre-Türkmen Central Asian cultures who created indigenous religious symbols as well and when they perished, and they all perished, they invariably took with them many of the true meanings of their symbols. These long forgotten artifacts and relics depicting early symbols were later found and resurrected by the Türkmen marauders who overran their land. They continued to incorporate the lost culture’s ‘dead’ symbols’, fusing them with symbols in their own textiles, thereby preserving them by reusing them. Slowly, they fused all their symbols together completing the changing morphology of their own symbols which were then assimilated into the Türkmen gül pool as the iconic symbols so pervasive in the Türkmen textile ornaments seen today, such as star clusters, star cross overlays, circles, rhomboids, serrated diamonds, pyramids with ‘eye lashes’, octagons, ram horns and many more. For millennia, Türkmen women continued to copy new symbols as weaver-copiers into their textiles even as they no longer really knew why, they just did it instinctively, always remaking them over into their own versions so they could call them their own.

Eventually they created an animist toponym layer for their symbols, renaming them after their own small animals, thus adding a folkloric animist personification layer over the symbols. They fused their ancient Türkmen steppe animist totems with symbols found on painted ceramics from numerous proximate pre-Türkmen Central Asian cultural ruins. Unusual alchemy. Charming as this was, it only made it more difficult to decipher any true original meanings of these inherited symbols now covered over with eponymous animal totem names, fertility cult symbols and zoomorphic figures that were native to the Altai Shamanic Türkmen steppe animist pagan religions. By casting these ancient symbols as their small animals, they made them their own, which is pure tribal animist totemism. By analyzing these names it gives us unusual and unexpected insights into the paradigm of these ancient Türkmen steppe peoples.

Türkmen women wove a sophisticated codex of symbols into the red rugs to portray a story of their empirical universe and their migratory patterns, symbolically reflecting their nomadic, spiritual and social structure, that protected them and their deep belief in the magic that surrounded them during their annual sojourn benevolently guiding them through their hungry steppe. It has been known for sometime in Turkmenistan that the crescent moon and star symbol was given to Islam by the Türkmen and not the other way around, and it’s displayed in the Turkmenistan national flag.

A description of the function of symbols in Türkmen çüwals

and to:rbas

The primary gö:l of each major Türkmen tribe was unique and only that tribe had the right to use it as their main identifying Tamgha (clan brand) unless they were defeated by another Türkmen tribe who then in turn gained the right to use the vanquished tribe’s gö:l. Conversely, the use of another tribe’s primary gül in a Türkmen çüwal or to:rba isn’t as restricted. The Türkmen çüwal was the main caravan cartage bag woven for use in both the caravan and the tent and was both utilitarian and apotropaic simultaneously. The çüwal’s güls so carefully arrayed in the field form a “living diorama” of the encampment in two dimensions but metaphysically unfolds into three. This can be seen when the çüwal’s güls are viewed from directly above, looking down. These primary güls symbolize the actual octagonal Türkmen öÿs inside the encampment, portrayed as slightly flattened octagons. Their tents were a microcosm of the macrocosm outside them, connecting everything outside the tent to everything inside the tent. Türkmen believed that they were directly connected to the cosmos and it was connected to them. Slightly different from a to:rba, a çüwal’s collective symbology is both a working metaphysical device and a symbolic model of their pagan shamanic cosmology. The çüwal’s design’s intricate and intuitive balance and symmetry meta-programmed the Türkmen subliminally by internalizing that balance allowing them to mitigate the deadly and irreconcilable forces in their own nature, which if allowed to activate, will in each situation, generate deadly hostility (Carl Jung). This balance was especially necessary to insure a peaceful co-existence between the males and females. Thus their intricate balance and symmetry generated 'a great demand for order’. Like opposing dragons, the only way both can avoid being burned is to get as close as possible and inhale each other’s flames.

Thoughts on Shamanic steppe animist religions

Türkmen weaving evolved as a biomorphic phenomena, like spiders weaving webs, and became their ethno-bio-pattern as living entities. Their rug’s were the ultimate combination of spirit and craft. Their lives were inextricably woven into their rugs as were the symbols of their universe, where all things are connected. The Türkmen venerated birth, death, valor, ancestors, rugs and the predatory skills of certain hunting birds (11th century). As steppe animists they believed their ancestor’s spirits lived in their animals whom they venerated and worshipped in return for various wishes granted, often treating animals better than humans. Türkmen were born on a rug, lived on a rug, died on a rug, and were buried with a rug laid over their grave (sometimes they were buried standing up, perhaps to face chthonic adversaries). Pre-Islamic, Mongol-Turkic Shamanic animist traditions persisted throughout the history of the Türkmen steppe peoples. The Shamans were sometimes their magnificent chiefs as well who conjured up the other worldly correspondent called the Blue Wolf or Jenni Jenni, whom they summoned during their trance induced rituals and incantations they performed for three days to heal a sick child or seek relief from catastrophes. They lived in a primal world of magic, where they were star energy harvesters, taking whatever star energy they could and channeling it for specific blessings necessary for their well being. They placed seven different to:rbas around the smoke flu (tüynük or oculous), a circular opening at the top of the dome of the öÿ, in order to collect star energy from the Pole star Polaris into each bag for good health, crops, hunting, successful fertility, etc.. Their beneficial star energy also flowed down the sacred wind ropes (ak ÿüps) suspended from the tüynük conducting positive star energy down to the ground below, reversing it’s negative polarity. They believed everything in the universe that happens is intimately connected to them and whatever happens too them

is connected to the universe.

The inner workings of red çüwals and to:rbas

The resplendently red Türkmen çüwal tells a story of perpetual seasonal migration through symbols that reveal a sophisticated model of connectedness to their magical world, incorporating the many layers of apotropaic spells, carefully measured and constructed magic, they cast through their eye-cracker amulets, talismanic devices and charms, all represented by and evoked from within their çüwal’s symbols. The channeling of star energy occurs through a repeating (repetition increases power) of ornaments conducting energy as binary movement through the on/off pulsing action of minor guard border’s ornaments, especially in the gyak stripes that horizontally cross the top opening lip of the çüwal. A perfect model of dynamic processes taking place in a straight line. 'Objects of one type setting each other in motion', (Prof, Yoni Sayfa, Turkmenistan).

The çüwal is the true ‘Book of Türkmen’ acting primarily as a metaphysical device for casting spells and evoking defensive magic. Like the Rosetta stone it is decipherable, it just hasn’t been done yet. My hypothesis is that the red çüwal doubles as a working three dimensional diorama of their encampment and a ‘star energy switchboard’! If you take the octagonal güls carefully arrayed in a red Téké çüwal’s center field and orthographically project them into three dimensions, when viewed from above, the güls actually become their eight sided tents or öÿs, each in perfect harmony with their opposite minor emblems. The reciprocal minor secondary emblems are necessary super-alternatives to the energy of the öÿ (even the tent’s posit as the sun) and the major primary gö:ls and is a critical female or negative contra-position, a necessary loose electron essential for correct balance in their Shamanic cosmology. The gö:l and the The octagonal öÿ symbol of their tent in the çüwal’s field are symbolically circled by the Sun star in it’s annual sojourn around the tribe as depicted in the complete outer border’s repeating sagdak emblems. The re-enacting of the Sun’s annual journey in the day and night sun circling all the way around the tribe is symbolized by the alternating light then dark Sagdak emblems (from Sogdiana) ancient symbol of the Sun star with it’s varying center motifs. The lower apron of a çüwal represents the foreground of the encampment which is a part of their sacred toprak dirt cult and commonly depicts symbols of flowers or gochanak tree variants like gapyrgas. In conclusion, the Türkmen red çüwal is an all encompassing device of working archetypal and metaphysical parts used to channel beneficial energy from the heavens to to their various specific needs. A natural phenomena of energy flowing from areas of higher concentration to areas of lower concentration.

Bridal fingers

Gelin barmak in Türkmen means ‘bridal fingers’. This repeated motif pattern resembles linked pentagonal forms with three straight sides and an apex top found lining narrow minor guard borders or the inside of primary gö:ls or güls in çüwals. They form a sort of electric fence which projects a defensive force field around those sitting in the center of the rug protecting them from evil. Literally warning evil to ‘get out’, ‘go away’ or ‘mind your own business’.

Potential brides were often selected for marriage based on their ability to weave as shown in their dowry presentation rug, which the bride to be wove herself to showcase her skills. Her presentation piece was usually a small bridal mat or an asmalyk, one of six to eight dowry rugs she will bring to the wedding, the rest were woven by the other women in her family. The bride to be prominently displayed her rug on the lead wedding camel’s flank often showing its back to better display the fineness of her weaving. When she reached the öÿ of her soon to be father-in-law, she would place her bridal mat down in the women’s section of the tent in the rear where she would sit and receive her girlfriends. Oral informants say while she wove her dowry rug the young bride to be would especially careful to avoid conversing with anyone for fear that evil spells might find their way into the conversation and therefore into the rug and into the marriage.

Real rugs

It is my opinion that the ‘ancient tribal meeting grounds’ were located in Kurdistan on the Old Silk Route where summer and winter silk routes converged in Central Asia and Asia Minor. Over several millennia many different nation’s groups, civil servants, tribes, merchants, traders, camel caravans with goods, etc., all came across from the Far East, India, China, Mongolia and Tibet to Kurdistan, where they met and exchanged an endless variety of ideas and symbols from all over the world. This interaction of so many disparate cultures, religious philosophies, ways of life, etc., for so long, eventually created the ‘real Oriental rug’s’ symbology which displays all the primary symbols from the world’s largest religions together with symbols from pre-historical Central Asian societies into a one universal rug symbology with universally transferrable rug symbols. It took a infinite amount of time to combine the world’s seven oldest religions’ symbols together into one ‘real rug’ symbology that says we are all a one universal religion. This is the basic tenet of the Türkmen belief system 'that all things are connected and affect each other.

What I called a ‘real rug’ forty five years ago, I now call Universal Sufism. ‘Real rugs’ reflect a symbiosis of earth’s major religions. ‘Real rugs’ were derived from an eternity of knowledge and ideas exchanged back and forth in the ancient tribal forums of Kurdistan and displayed a syncretic symbol compilation of each culture using the Old Silk Route as an ultimate transferrer of knowledge. Driven by this, the ‘real rugs’ I discovered forty years ago are a truth driven record of complete universal symbology. I first recognized the so-called ‘real rugs’ because of the continuous appearance of the same symbols from so many different religions in so many different Oriental rugs, like the cross being identified with Christianity, but still found in rugs that have nothing to do with Christianity (unless of course, maybe they do?). I could visually pick out a compilation of the symbols from each major religion’s in each rug. Persian symbols, Hindu, Christian, Chinese, Tibetan, Buddhist and Zoroasterian symbols, each clearly discernible along with symbols borrowed from the southeast Turkmenistan’s pre-Türkmen Central Asian cultures like White Huns, Sistan, Sumer, Morgiana, Sogdiana, Scythian, Bactrian, Sarmatian and the Zoroasterian ‘faravahar’ to name but a few. Shortly thereafter, I had my second epiphany that all rug symbols were universal and transferrable. The same symbols appeared in every weaving groups’ rugs, not just Türkmen rugs. In other words, the ‘ancient tribal meeting grounds’ symbols were proven to be universally transferrable (symbols without borders). Therefore symbols in a Caucasian rug were not exclusive to the Caucasus, but also found in Anatolian, Türkmen or Chinese rugs for that matter. In fact the symbols that emanated from the ‘ancient tribal meeting grounds’ were completely universal and appeared in all the weaving groups’ textiles. There seemed to be a common bedrock to these ancient oriental rug symbols that goes beyond their countries or borders or time.

These ancient symbols seemed to transcend ownership. They seemed to have a life of their own. They came from an unknown place that had very little to do with the world yet when they appeared, no matter which group’s rugs they appeared in, they seemed to reflect a higher order of meaning, a connectedness outside of normal perception. Where did these symbols come from? What did they mean? How did they get there? They were displayed in each real rug, yet no one ever laid claim to them. The truth is, I think, that no one knows yet. In fact, a Türkmen Çemçe gö:l does not resemble a spoon, yet Çemçe means spoon. Perhaps a cemce to:rba is called a spoon bag because a spoon fits in it (a use name). Just as a spindle bag is called an igsalyk to:rba because a spindle fits into it? So if you carry shoes in it, it would be called a shoe bag? There is obviously no connection between a Çemçe gö:l and the word Çemçe. There is a connection with a igsalyk to:rba and a spindle bag because ‘ig’ refers to a spindle and spindles do fit in it, but then again so can other things. Türkmen to:rbas were often informally named for their different uses which is not unusual for a tribe to do and when that use changes, the name also changes, so a ‘use’ name is limited only by the number of uses.

Exhibition Rug Photos with Their Technical Descriptions

Click rug photo to enter for tech descriptions

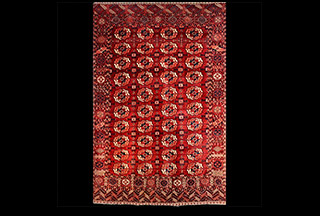

Ca. 1880

Ca. 1870

Ca. 1880

Ca. 1880

Ca. 1880

Ca. 1885

Ca. 1870

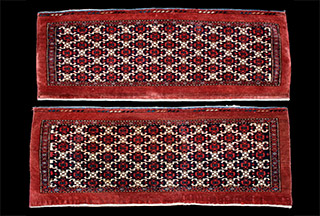

Türkmen Ak Suw torbas (a pair)

Ca. 1870

Ca. 1875

Ca. 1890

Ca. 1875

Ca. 1870

Ca. 1875

Ca. 1870

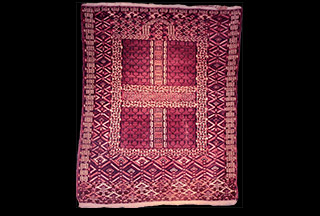

Ashyk To:rba

Ca. 1870

Ca. 1860

Ca. 1865