The Clay Stewart Collection of 19th Century Türkmen Textiles

The Red Rugs of the Transcaspia

Since the dawn of time, in the dimmest recesses of Central Asian history, there roamed pastoral tribes of fierce Türkmen nomads, in an area so secluded and remote, that only today are we learning about them. For untold millennia, they pastured and quartered in incredibly isolated settings and evolved a remarkable material culture, so unique that it would make science fiction movies like Star Trek seem mundane by comparison. Geographically cut off from the rest of the world, they became brilliant at animal husbandry, breeding sheep, horses and goats, for their material culture, enabling their seasonal migrations. They adapted limited local resources to create carefully wrought, stunningly beautiful, hand woven, utilitarian textiles, that lived up to the tests forged by their impossibly hard environment. Through skills evolved over thousands of years of uninterrupted trial and error they wove plain wool into the strikingly beautiful moveable architecture, essential for their daily survival in a dangerous and often hostile environment. They acquired madder, indigo, silk and cotton through a complex system of bartering and networking, both local and far reaching. All nomad textiles were woven by women, who infused the Female Goddess fertility cult into the rug’s symbols. As they had no written language, textiles became their secret book of instructions with their own language of symbols.

An old Armenian master threw a book to the floor and loudly cried out…“Do you want to learn books or do you want to learn rugs? This is the book! This is the book!”, he exclaimed, pointing to a rug.

They had no written language, yet developed a non verbal language of archetypal symbols encoded in their textiles, that throughout time, meta-programmed them. The theory that in the 10th century Sufi monks from the Aral Valley came into Turkmenistan and gave the ancient symbols to the Türkmen (possibly Salyr) and with them the true knowledge of the meaning of these ancient symbols disappeared.

Türkmen women continued to copy the symbols (as weaver-copyists) for a thousand years, no longer knowing their meaning or really knowing why. Eventually, they named these lost symbols after their small animals in an folkloric oversimplification of their meaning. Charming as this was, it made it even more difficult to decipher the mystery of the language of their rugs. The true meaning of the symbols was covered with a folk layer and most likely fertility cults. By casting these ancient unknown symbols as small animals they made them their own.

As Türkmen women continued to weave (unbeknownst to them) a codex of their empirical universe, and their migratory patterns, reflecting their spiritual and social structure, which carefully protected them and their deep belief in the magic that surrounded them during their annual sojourn; benevolently guiding them through a dangerous world.

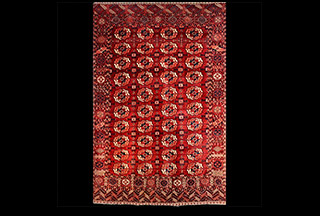

The rug’s major go:ls are unique to each of five major Türkmen tribes. The go:ls of each major tribe are heraldic and only that tribe has the right to use that emblem (tamga). Unless they are defeated by another tribe who then has the right to use the vanquished tribe’s emblem, if they wished.

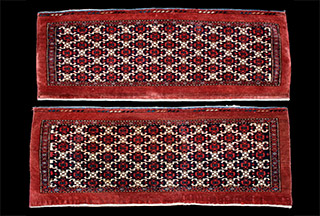

Their cu:wal rug is a smaller (3x5) transport bag where the face is knotted and displays indigenous symbols of a particular tribe. The symbols also depict a “living” diorama, an encampment model, in two dimensions, but unfolds into three dimensions. Showing their octagonal oy (tent), and even symbolically mapping their perennial migration. A device that shows everything, even selecting variations of red colored abrash to symbolize their sundowns at a distance. The design includes an intuitive balance and symmetry, which Türkmen subliminally absorbed, meta-programming themselves to get along, mitigating fierce dynamic inner relationships with each other, to ensure a peaceful co-existence between males and females. They venerated birth, death, rugs and mimicked the spirit of predatory birds (11th century). They were thieves, brigands, stealers of wives and dealers in Persian slaves. They were also possibly the best mounted cavalry in Asia in the 18th through the19th centuries. And they could slit a throat with the same precision they wove their finest rugs with.

Their weaving evolved to a biomorphic phenomena, like spiders weaving webs, and became their ethno-bio pattern as living entities. Their rugs became the ultimate combination of spirit and craft. Their whole lives were one with the rug and with their universe, where all things are connected. They were born on a rug, lived on a rug, and died on a rug, then were buried (sometimes standing up) with the rug laying over their grave. Shamanist and animist traditions continued. Their magnificent chiefs were often Shamans who conjured up their other worldly correspondent, the Blue Wolf Jenni, summoned during powerful trances they endured for days in order to heal their sick. They lived in a primal world of magic where they were star energy harvesters, which they used for protection and blessings for everything of importance. They placed seven various symbolic energy collection bags or to:rbas for health, for good crops, for good bird hunting, for successful fertility, etc., around the smoke flu (tuynuk) in the top center of their tent in order to collect the star energy from the North Pole star, Ursa Major. This energy also was channeled down through their wind ropes (ak yups), from the open flu, at night, to the ground below to energize the ground underneath them with positive star energy.

Their rugs told their always changing story in cipher. The designs of their transport bags (cuwals) were composed of a sophisticated complex model incorporating extra layers of apotropaic spells, carefully measured and constructed magic cast through amulets and talismanic devices and their effects. The rug is now their book and their device for casting spells. It is also a diorama of their camp. If you take the octagonal guls in the cuwal’s field and orthographically project it into 3 dimensions, those guls become the eight sided tents in a camp, each in perfect harmony with their minor emblems, which represent a consummate super-alternative to the energy of the tents or even their posit as suns; a necessary loose electron, thus balancing out the universe. The tents are encircled by the day/night, light/dark image of the Sun as it makes its yearly journey around the tribe. The apron at the bottom of the cuwal represents the foreground in front of the camp, which is sacred and part of their dirt cult and usually shows flowers in the design. An all encompassing device of working archetypal symbols that represents that one tribe alone. Tribal counts by Russian army intelligence agents in the 1840’s show one Teke Türkmen tribe in the Transcaucasus with 50,000 tents, each with possibly five or more people per tent, thus having 250,000 nomads in one tribe, a moving city.

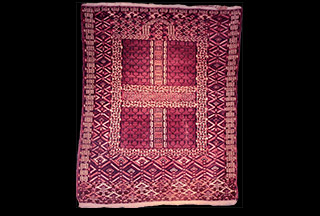

Gilim barmak are repeating pyramids that formed a sort of electric fence producing a line of protective energy, surrounding whoever is sitting in the center of the rug, which in the design represents the tribe itself, as represented by the diorama, and as well, the bride herself. Many brides were selected by the fineness of her dowry rug which she wove to showcase her skill.

This Bridal mat was prominently displayed on the wedding camel and when she reached the tent of her new father in law she placed the Bridal mat down in the women’s section of the tent and sat on it while she received her girlfriends.

Ca. 1880

Ca. 1870

Ca. 1880

Ca. 1880

Ca. 1880

Ca. 1885

Ca. 1870

ak suw to:rbas

Ca. 1900

Ca. 1875

Ca. 1890

Ca. 1875

Ca. 1870

Ca. 1875

Ca. 1870

Ashyk To:rba

Ca. 1870